Items

Template

Exhibition_Histories_Template

-

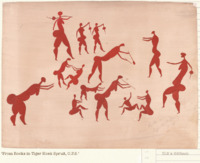

Ku-'ku-curra!

Extract from: Skotnes, P & Stow, G.2008. Unconquerable Spirit : George Stow’s History Paintings of the San . Johannesburg, South Africa: Jacana. 34 -

Ku-'ku-curra!

Extract from: Skotnes, P & Stow, G.2008. Unconquerable Spirit : George Stow’s History Paintings of the San . Johannesburg, South Africa: Jacana. 34 -

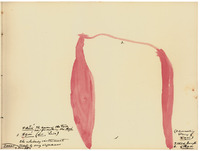

Whirring instrument

Description : 1. xam (Lit., "Lion") The whirring instrument made by my informant., 2. stick-handle of xam, (3. connecting string of xam), ≠nin, The name of the tree used for making the xam -

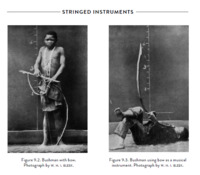

Bows

Page from Kirby, P. 1934. Musical Instruments of the Indigenous People of South Africa . Third edition. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. -

|uma

“|uma was one of the two younger !kun boys who arrived in Mowbray on the 25th of March 1880. |uma (and the youngest boy Da) were placed in the Bleek and Lloyd household after permission was granted by the Cape ‘Native Department’. Lloyd notes on the reverse of a photograph of |uma (in the collection of the NLSA) that |uma is ‘apparently’ between 12 and 14 years of age. |uma left Mowbray on the 12th of December 1881 and was found employment by an official of the ‘Native Department’ Mr George Stevens. He was not able to contribute much narrative to Lucy Lloyd, and the contributions he did make are limited to some 58 pages of dictation, but he did many drawings and water-colours depicting examples of fauna and flora from his homeland” (The Digital Bleek and Lloyd 2021). -

Bows

Plate from Kirby, P. 1934. Musical Instruments of the Indigenous People of South Africa . Third edition. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. -

Bows in Stow

‘Shewing the Development of Stringed Instruments from the Nushman-Bow’ Watercolour, University of Cape Town. -

Bows

The Kirby collection, housed in the South African College of Music, UCT consists of more than 600 musical instruments, most of which were used in southern Africa before 1934, many pre-dating urbanization. Starting as early as 1923, the Scottish historian and musicologist, Percival Kirby, then Professor of Music at the University of the Witwatersrand (and a colleague of Raymond Dart), observed the music cultures of indigenous South Africans through a series of field trips conducted during university vacations (Nixon in Kirby 2013: ix). He collected these instruments and categorised them using a Western system for classifying musical instruments and the principles on which they were based. Stipulating three categories (percussion - ‘rattles and clappers’, ‘drums’, ‘xylophones and sansas’, and ‘bull-roarers and spinning-disks’; wind instruments – ‘horns and trumpets’, ‘whistles, flutes, and vibrating reeds’ and ‘reed flute ensembles’; and stringed instruments) these divisions and their subsequent curation in the SACM encourages a ‘comparative’ viewing framework. Comparative displays were very popular in anthropology in the 19th and early 20th century and grouping objects sourced from various communities worldwide according to ‘type’ in relation to western versions served to enforce ideas of Social Darwinism, depicting a scale of development from what was viewed as ‘primitive’ objects to the more evolved Western versions. -

Gubo

Page from: Williams, G. 1902. The Diamond Mines of South Africa: Some Account of their Rise and Development. New York, London: Macmillan. -

Bambatha Rebellion

“We understand that this drum was played during the 1906 Bambatha rebellion against British rule and unfair taxation in what was then Natal. Between 3 000 and 4 000 Zulus were killed during the revolt some of whom died fighting on the side of the Natal government. More than 7 000 were imprisoned, and 4 000 flogged. King Dinizulu was arrested and sentenced to four years imprisonment for treason. The belt that the drummer would have been used to wear it is now broken, but the drum would have been used as accompaniment to ingoma dancing, which was/is performed with drums, whistles and often full regimental attire”. Micheal Nixon, former Curator of UCT’s Kirby Collection (Humanitec 2015) -

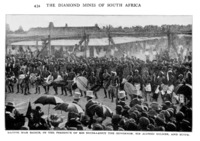

War dance

Plate from Williams, G. 1902. The Diamond Mines of South Africa: Some Account of their Rise and Development. New York, London: Macmillan. -

Royal Pen

Pen used by Queen Elizabeth when she signed the visitor’s book in the UCT library in 1947. -

Diamonds Swallowed

Plate from Williams, G. 1902. The Diamond Mines of South Africa: Some Account of their Rise and Development. New York, London: Macmillan. -

The Imperial State Crown

Queen Elizabeth II wearing the Imperial State Crown after her coronation -

"a simple, dignified and deeply moving ceremony"

“In 1947, on the brink of the fateful election that saw the coming to power of D.F. Malan and the imposition of the apartheid system, the British Royal family spent just over two months touring the Union of South Africa. On 22 April 1947, two days before the end of the tour and the Royal departure, UCT conferred an honorary Doctorate of Laws on the then Queen Elizabeth. The Argus describes the event as: ... 'a simple, dignified and deeply moving ceremony ... in which Her Majesty occupied the centre of the stage as the Chancellor of the University, General Smuts, conferred the degree upon her' (The Argus, 22 April 1947). The report noted that, 'Long before the doors of the Jameson Hall were opened, professors, lecturers and students thronged the steps leading to the Hall. The brilliant gowns of the professors, mingled with the black undergraduate gowns of the students, formed a spectacle, which must have been one of the most colourful of the whole royal tour' (The Argus, 22 April 1947)” (Bloch 2016: 172). -

Cape Town Diamond Museum (Wallpaper detail)

A detail from the wallpaper used outside the Cape Town Diamond Museum in the V&A Waterfront. -

Cape Town Diamond Museum (Wallpaper detail)

A detail from the wallpaper used outside the Cape Town Diamond Museum in the V&A Waterfront. -

Working conditions

Gardner Williams writes about the living conditions of the mineworkers in one of the chapters (‘Workers in the Mine’) of his book – referencing the divided public opinion about it: One such was a member of the Legislative Assembly of Cape Colony, who came to Kimberley to investigate the conditions of life and treatment of the natives in the compound. On arriving at De Beers Compound, in company with his wife, he first impressed upon the natives whom he met that he was a member of the Cape Colony Legislative Council. He had come to the fields in their behalf, and he wanted them to tell him freely everything of which they had to complain. With the aid of an interpreter he interviewed a number of natives in the compound, asking searching questions about their treatment. One native told him that he had been working for eight years in the mines and had been outside the compound only three or four times in all that period. When asked if he was well treated in the compound his answer was, "" If I didn't like it, Baas, I wouldn't be here." Before leaving, the legislator said that he was glad to have the opportunity to inspect fully the operations of the compound. From what he had heard he had been much opposed to compounds, but he now saw with his own eyes that he was wrongly informed, and henceforth he should be a strong advocate of the system. Yet a year or two later, when questions affecting De Beers Company and the compound system arose in the Upper House, this gratified member was one of the first to denounce the system in an intemperate speech. (Williams 1902: 448 – 449) -

The Drawbridge, from Carceri d'invenzione (Imaginary Prisons)

Trained as an architect, the master printmaker Giovanni Battista Piranesi, created his Imaginary Prisons (Carceri d’invenzione) series in the mid to late 18th century. This series of darkly foreboding interior scenes, which depict over-lapping archways and stairways that seem to lead nowhere, influenced the work of Lord Byron, Escher’s impossible geometries, as well as Poe 's classic tale of horror, The Pit and the Pendulum. -

Workers in the mines

“In the mines operated by the De Beers Company alone, more than eleven thousand African natives are employed below and above ground, coming from the Transvaal, Basutoland, and Bechuanaland, from districts far north of the Limpopo and the Zambesi, and from the Cape Colony on the east and the south to meet the swarms flocking from Delagoa Bay and countries along the coast of the Indian Ocean, while a few cross the continent from Damaraland and Namaqualand, and the coast washed by the Atlantic. The larger number are roughly classed as Basutos, Shanganes, M'umbanes, and Zulus, but there are many Batlapins from Bechuanaland, Amafengu, and a sprinkling of nearly every other tribe in South Africa” (Williams 1902: 412-413). -

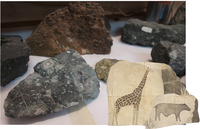

Stow visits the Mantle Room

A detail from a painted sketch by Stow that he used in creating his collages, collaged onto a photo of the Mantle Room collection of kimberlite specimens. -

The Diamond Mines of South Africa: Some Account of their Rise and Development

Front matter from Williams, G. 1902. The Diamond Mines of South Africa: Some Account of their Rise and Development. New York, London: Macmillan. -

The Mantle Room

“The initial impetus for establishing a collection of mantle materials for research purposes in South Africa was provided by Gardner Williams and his son Alpheus Williams in the late 19th and early 20th century. These two American mining engineers shared a great interest in the mining methods and geology of the South African kimberlite-hosted diamond mines they were supervising. Each wrote books on the subject and the two men assembled a collection of scientifically interesting rock samples and minerals from the mines. Subsequent to the death of Alpheus Williams, the Williams family donated this collection to the Geology Department at UCT for teaching and research purposes” (Department of Geological Sciences 2021). -

Looking for kimberlites

A kimberlite specimen from the Mantle Room, superimposed on a detail from Stow’s Geological Survey of Griqualand West -

The Mantle Room

“The University of Cape Town houses a collection of upper mantle-derived materials (mantle xenoliths and xenocrysts, kimberlites and related rocks and megacrysts, as well as deep crustal xenoliths) that is most likely the largest of its kind. The collection was assembled over the past 50 years and has been and continues to be an invaluable and irreplaceable resource for mantle research. Informally named the “Mantle Room” collection, it is maintained under the auspices of the Department of Geological Sciences” (Department of Geological Sciences 2021).