Essay

The early 1990s was a time when many things that had not been possible suddenly became possible. It seemed as if museums were embracing change. They were open to being more self-critical – and to looking at their collections critically.

Dr Patricia Davison

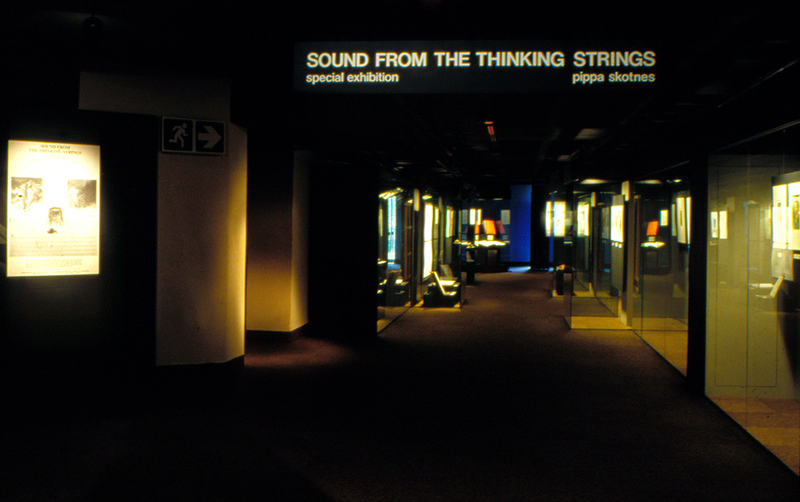

Wandering through the different galleries of the South African Museum in 1991, visitors would at some point have found themselves in a space similar to the ethnographic hall they had passed through on entering the museum. Gathering and hunting bags, bows and arrows, animal hides, body adornments, musical instruments, ostrich eggshells and a range of excavated objects were displayed in a long corridor leading off from the whale well. Most of these objects had labels that stated the object’s presumed use and the sites from which they had been recovered, affirming their affiliation with the content on display in the ethnographic halls and their home within the disciplines of archaeology and anthropology. So far so familiar, visitors might have thought.

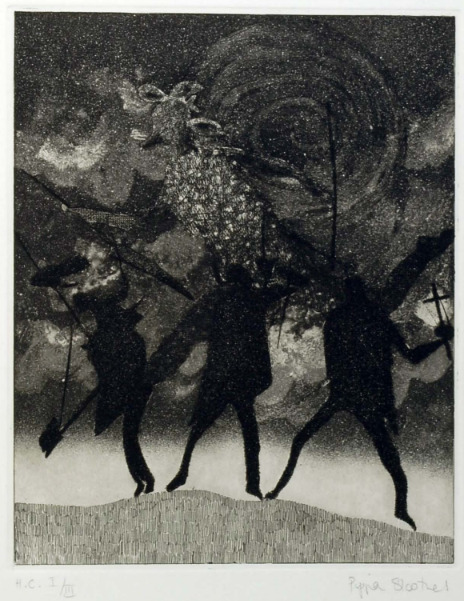

However, these objects were not the only things on display in this space: hung on the walls to accompany the object groupings were historical notes, documents and photographs and a series of contemporary etchings by Skotnes depicting subject matter that echoed the objects on display – a visual reassurance for visitors (like a label confirming what you think you are looking at) were it not for the strange context in which the objects in the etchings were situated. An animal hide on display on a plinth was accompanied by an etching of a group of figures seeming to hover between animal and human form. In another etching, similar therianthropic figures wield musical instruments (echoed by the instruments on display), playing them up to a sky in which animal forms float against entoptic spiral shapes. On another wall, an etching of a hunting or gathering bag was surrounded with similar bags from the museum collection, hung on the wall on either side of it, while in another etching further along the wall, a similar bag hovered in the sky above a man-made shelter on the ground.

Pages containing poems and texts – essays, on closer inspection – written by a historian, an archaeologist and an artist-curator and a ‘foreword’ written by an evolutionary biologist also filled the walls. In the middle of the exhibition, a book on a plinth revealed, when paged through, the same pages as those dispersed across the walls. This ‘special exhibition’, as the vinyl above the doorway declared it, was Sound from the Thinking Strings, curated by the artist-curator Pippa Skotnes.

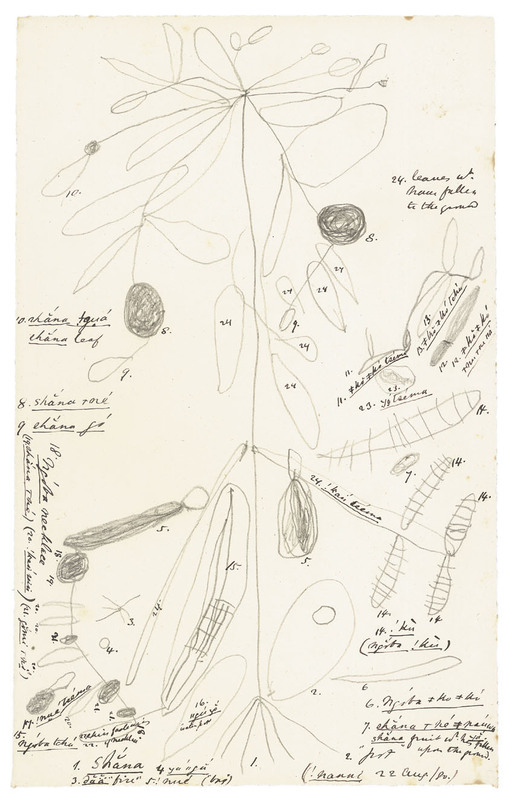

Sound from the Thinking Strings is comprised of twenty etchings created by Skotnes that drew on southern San mythology, archaeological and historical research and rock paintings; poems by the late poet Stephen Watson that interpreted extracts of nineteenth-century recordings of |xam cosmology compiled in the Bleek and Lloyd archive and pre-selected by Skotnes; and historical and archaeological contextualisations of these recordings in the form of essays by archaeologist John Parkington and historian Nigel Penn. The exhibition also displayed associated visual material that Skotnes sourced from the UCT and State Archives, the UCT Archaeology Department and the SAM.

Skotnes admits that the politics of representation posed a problem for her from the start when working with this subject matter (Skotnes 1991: 27). The rich collection of San myths and legends, poems, oral folklore and personal histories that make up the Bleek and Lloyd archive provide access to the cosmologies and complex social structures of a people denied these attributes in the colonial records, but Skotnes remained cognisant that this record was the interpretation of the two Europeans who recorded and transcribed the interviews conducted with the San informants (Skotnes 1991: 27). As such, the materials could not be seen ‘merely as a medium for communicating facts that could be observed in other ways’ (MacLuhan 1962; Foucault 1974; Derrida 1976; Thornton in Skotnes 1991: 27) and could not or should not be represented in such a manner. To address what could, in the scope of this thesis, be understood as Lloyd and Bleek’s ‘insider views’, Skotnes formulated a methodology that enabled the inclusion of other interpretations, both scholarly and imaginative, and collated these views in a book and a physical space, opening up these materials and their interpretations even further by presenting them to the diverse publics of the SAM.

Skotnes commissioned essays from UCT lecturers Parkington and Penn, academics who have both conducted extensive research on these hunter-gatherers in their respective disciplines of archaeology and history. Parkington’s archaeological research has shed light on the relationship between home and hearth and the rock paintings that populate shelter walls, while Penn’s historical work has provided an understanding of the northern Cape frontier in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century and of the clashes that occurred between the white settlers and the San . Skotnes also sourced a range of archaeological materials from UCT’s Department of Archaeology and the SAM and historical material from the university archives and the State Archives. Her inclusion of these materials and the academic essays highlighted an interesting tension between these separate but related components of academic research.

In conducting research, both the archaeologist and the historian are reliant on the material evidence they discover or source and then study, be it material gathered from a digging site or the various documents and photographs held in the archives. These are, in fact, the primary sources from which these disciplines make their deductions or inductions (Renfrew & Bahn 2005: 119–121). The physical reality of these materials is, however, normally omitted from the end product of research, which usually takes the form of research papers presented at conferences, of articles in academic journals or as published books. As textual documents, they translate primary materials into words, descriptions and two-dimensional images, which highlight particular aspects of the objects or archival documents that support their topic of research. By using the medium of the exhibition, which not only allows the joint presence of text and objects but foregrounds it, Sound from the Thinking Strings reinstated this relationship by displaying the essays and the objects, facilitating a different experience of research that included seeing and experiencing as an additional means of dissemination.

Skotnes also included creative interpretations of the archive in the form of poems and a series of etchings. For the poems, she approached Stephen Watson, a poet and lecturer in UCT’s Department of English, and asked him to undertake ‘translations’ of a selection of stories she had made from Bleek and Lloyd’s English versions of the |xam and !kun texts (Skotnes 2007: 48). Watson tried to remain as true as possible to what he termed the ‘spirit’ of the San stories selected for him and admitted in a newspaper interview that being involved in the project had opened his eyes to the rich culture of the people wiped out by the white settlers at the turn of the century, stating that no book or poem could begin to right these historical wrongs (Holzhausen 1991). In the same article, he expressed his wish that these poems would enable at least ‘some echo of the San's presence’ to be heard (Holzhausen 1991). By including Watson’s poems in the exhibition and book, Lloyd and Bleek’s interpretations were extended and given a contemporary voice, adding another perspective to the archaeological and historical views represented by the essays and objects (Skotnes 2007: 48).

Skotnes’s own visual interpretation of the history and cosmology of the |xam formed the last component of this interdisciplinary endeavour and constituted a visual component that drew together the various strands of disciplinary interpretations and presented a perspective on the |xam life she felt ‘was missing from the other interpretations’ (Skotnes 1991: 30). In these images she drew freely on San mythology, accounts of |xam life recorded by Lucy Lloyd, historical and archaeological research and images from rock paintings in a landscape setting. She writes in her preface that these etchings were direct attempts at ‘inverting the museum dioramas’ in the ethnographic halls close to the exhibition and which, through their display of the San’s body casts, rendered them closer to specimens of biology than as members of a highly developed culture (Skotnes 1991: 52). By creating images that combined shamanistic rituals, entoptic spirals, plants, hunting bags, bows and arrows, snakes, eland-shaped rainclouds, colonists, musical instruments, shelters and therianthropic shapes, Skotnes eclipsed the static narratives of the dioramas and the object labels in the exhibition, placing them in a context in which their metaphysical qualities were celebrated more than their physical qualities. These prints stood in striking contrast to the other exhibits, which framed the San as physical types, and they challenged viewers to confront the reality that the San had a rich history and cultural and social life.

These interpretations of the life and history of the San expanded the archive and highlighted the limits of any single understanding and interpretation of this subject matter. Moreover, by conflating timelines (a nineteenth-century archive with present day research and material), Skotnes drew explicit attention to the contingency of understanding and interpretation. Sound from the Thinking Strings seems to propose that the only way to represent the many dimensions of |xam life is through the amalgamation of various component disciplines – those of the artist, the poet, the historian and the archaeologist (Skotnes 1991: 30). The poems, prints and historical and archaeological essays worked together to create associations with one another, each adding the understanding of the other (Skotnes 1991: 30). In addition to drawing together these different disciplinary views, the exhibition also strove to address ‘the false dichotomy between the visual arts, literature and the sciences’ (I.B. 1992) by creating an interplay between them in both the exhibition and the book. This latter incentive was one of the founding principles of the Axeage Press, an initiative started by Skotnes and her colleague at the Michaelis School of Fine Art, Malcom Payne, and artist Alma Vorster.

Established two years prior to the exhibition, the Axeage Press published handmade artist’s books with an inter-disciplinary interpretation of a subject of South African culture. The publication of these artist’s books was only the first part of the process, however; the second part was to stage an exhibition in which both the book and its associative material were curated by the artist-editor of the book. These publications challenged the general understanding of what constituted ‘a book’ and, through their execution, content and display, asserted that a book could be an artwork. This new category of the book created by Skotnes and Payne was, however, not readily accepted by insiders of the written word, and Skotnes was sued by the National Library for free copies of Sound from the Thinking Strings under the Legal Deposit Act. The library maintained that a book could not be an artwork and that Sound from the thinking strings was not exempt from the Act. The much-publicised court case eventually found in favour of Skotnes. Sound from the Thinking Stringswas the first publication of the Axeage Press.